Welcome to Kinship America

In early 2021 a group of organizations convened by the Ohio Federation for Health Equity and Social Justice and the Ohio Grandparent and Kinship Coalition, met virtually to discuss the needs, concerns and issues that kin caregivers face when they step forward to care for their relative children.

These organizations represented the following states in this initial meeting: The Children’s Home Network of Florida; Kinship Resource Center, School of Social Work at Michigan State University; Children’s Home Society of New Jersey; Sisters of Charity Foundation of South Carolina; HALOS of South Carolina; Institute for Child Success of South Carolina; and Vermont Kin as Parents.

As discussions continued, it was determined that a very simple tool was needed which could identify the services each state provided to kin caregivers. There was consensus that the document had to be reader friendly while highlighting the vast differences in supporting kin across states. It was agreed that the best format for this information would be a scorecard.

Additional states joined as news of the monthly conversations were shared with those engaged in working with kin families. It was decided that the scorecard should be released at a national event. It was decided that as a recognition of Grandparent/Kinship Month, the group would work to convene a virtual National Town Hall.

Our Mission

Lay and strengthen the foundation for the beginnings of an enhanced network of national, regional, and state kinship advocates.

Educate policymakers, Legislators, and the general community on the challenges (financial, social and emotional) of kinship care.

Promote the creation and/or expansion of programs and policies that support kin in their efforts to keep the children out of the formal out-of-home placement system “foster care”.

Lay and strengthen the foundation for the beginnings of an enhanced network of national, regional, and state kinship advocates.

Educate policymakers, Legislators, and the general community on the challenges (financial, social and emotional) of kinship care.

Promote the creation and/or expansion of programs and policies that support kin in their efforts to keep the children out of the formal out-of-home placement system “foster care”.

NEWS AND EVENTS

Philadelphia

Inside Philly’s hidden foster care system, where parents ‘voluntarily’ give up their children

Parents report feeling coerced into accepting the agreements: Place the child here, they’re told, or we’ll take them into foster care.

In fall 2021, Tytianna Hawthorne received a phone message from an investigator with the Philadelphia Department of Human Services: Someone may have abused her 1-year-old daughter.

The investigator was acting on a confidential tip to ChildLine from a caller who said a photo of Su’Layah on a social media account showed “hookah charcoal burn marks” on Su’Layah’s inner thighs.

Hawthorne, a first-time mother at 20, had spent time in foster care herself and had no love for the system. She also knew DHS had the power to take away her child. She hoped that the evident good health of her daughter, Su’Layah Williams, would speak for itself, and she called the investigator back.

She told the investigator she first discovered the marks when her daughter returned after a weekend visit with her father. She treated them with Neosporin. Hawthorne said that money was tight, and that she and her daughter had been living with family members and friends.

PLANTSVILLE, CT – MARCH 06: Cameron Comparone, 2 1/2 places a stone on the grave of his father Benjamin Comparone, 27, as friends and family gathered on March 6, 2016 in Plantsville, Connecticut to commemorate the first anniversary of Benjamin’s death from heroin overdose. The nationwide heroin epidemic has overwhelmed many small towns and suburban communities, with heroin overdose deaths quadrupling, according to the Centers of Disease Control. The victims’ families, many of them facing stigma themselves, are increasingly going public to lobby for greater access to recovery programs and bring awareness of addiciton as a disease, not a moral failing. The CDC says that of first time heroin users, some 90 percent are white and 75 percent had used prescription pain killers before turning to heroin. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Hundreds of thousands of parents died from drugs. Their kids need more help, advocates say.

More than 321,000 children have lost a parent to a drug overdose, a recent federal study found.

Every day, 8-year-old Emma sits in a small garden outside her grandmother’s home in Salem, Ohio, writing letters to her mom and sometimes singing songs her mother used to sing to her.

ACF-OFA-CB-DCL-24-01

December 30, 2024

Dear Colleague:

The whole of the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) is committed to improving the overall wellbeing of families by preventing child maltreatment, and values doing so through collaborative efforts that support and stabilize families and protect children. To clarify how this commitment can be realized by states and localities, the Administration for Children, Youth, and Family’s (ACYF) Children’s Bureau (CB) and Office of Family Assistance (OFA), both within ACF, offer this guidance and our ongoing support to states, territories, and tribal grant recipients as they address the basic economic needs of families as an evidence-informed strategy to prevent child maltreatment and ensure children remain cared for in their homes or with relative caregivers.

Read More

Poverty itself does not equate to maltreatment or neglect. The lack of income or economic supports, however, may increase the risk of material challenges that lead to significant stress within families or challenges for parents in providing for their children’s basic needs. This stress can hinder children’s cognitive development and/or increase the risk of parents’ inability to care for their children adequately, a risk which could be best mitigated with concrete economic supports.

i The differentiation between a family’s inability to provide versus maltreatment is a top priority of ACF. In order to provide families with concrete financial supports and decrease the risk of the inability to provide, states, territories, and tribal grant recipients may use Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds to increase and support protective factors for children within their families and communities in ways that prevent their involvement in the child welfare system.

We recognize, however, that across states, territories, and in tribal nations, the administration of the TANF grant and the child welfare program are often not situated within the same office or roles. Coordinated planning around program design and budget must occur across all jurisdictional offices and roles to ensure a holistic approach to support families’ well-being. Both OFA and CB encourage states, tribes, and territories administering both programs to collaborate on a comprehensive prevention framework that centers investment in families’ economic well-being, while operating within the requirements of each program. This approach can facilitate intentionality in braiding available supports to stabilize and strengthen families.

Background

TANF funds may only be used in a manner reasonably calculated to accomplish one or more of four broad purposes outlined in the TANF statute, 42 U.S.C. 601(a)(1), or in accordance with the grandfather clause at section 601(a)(2). Within this framework, TANF programs provide a range of benefits and services that can serve as a critical support to families experiencing economic hardships.

The first statutory goal of TANF, known as TANF purpose one, is to provide assistance to families experiencing financial need so that children can be cared for in their own homes or with relatives. States and tribes currently report using TANF funds for activities reasonably calculated to achieve TANF purpose one, including targeted prevention and reunification interventions in the child welfare system. Certain activities promoting prevention, reunification, or kinship care include parenting skills classes and supports, supports for parents preparing for reunification, and providing concrete and economic supports to prevent removal from home or to support kinship caregivers.

Nationally, 1 out of 5 federal TANF dollars are directed by states and tribes to child welfare activities, but on a state-by-state basis, the expenditures can be anywhere from 0 to 52 percent of federal dollars spent. A biannual survey conducted by Child Trends reports that TANF spending by child welfare agencies equaled approximately $2.6 billion in state fiscal year (FY) 2020.

ii ACF’s collection of TANF financial data shows that states spent $2.7 billion in federal TANF or state Maintenance of Effort (MOE) funds on child welfare services in federal FY2023, including foster care and child welfare authorized solely under prior law, which accounts for 8 percent of all TANF and MOE funds used in that year. Forty-three states reported spending some of their TANF or MOE funds on child welfare services and, of those, in 12 states child welfare services represented 20 percent or more of their TANF or MOE spending.

Below, we offer examples of where a child welfare service can be reasonably calculated to meet a TANF purpose, and therefore be an allowable use of TANF funds.

iii Jurisdictions may use TANF federal or MOE funds for certain family stability, prevention, and reunification services for families eligible under TANF purpose one. OFA and CB are encouraging states, territories, and tribes to leverage data and practice experience to identify opportunities to collaborate even further toward the economic stability of families to prevent unnecessary removal of children from their families’ homes whenever possible, prioritizing circumstances where a lack of financial resources is the root cause of the potential child welfare involvement.

Families experiencing both intergenerational poverty and immediate economic shocks are at greater risk of child welfare involvement.

iv Children living in families with a low socioeconomic status (SES) have rates of child maltreatment that are five times higher than those of children living in families with a higher SES.

v Similarly, research has articulated the negative impact of state policies that restrict TANF access (such as time limits of less than 60 months, severe sanctions for not meeting work requirements, work requirements for mothers with children under 12 months, and suspicion-based drug testing of applicants) on child well-being and safety trends.

Access to appropriate economic supports influences whether a parent or caregiver is available and able to support their child’s needs when factors that are associated with child neglect such as low income, income instability, food insecurity, or lack of health insurance exist.

vii A recent literature review detailed the consistent correlation between providing economic supports and preventing child welfare involvement.

Research simulating the effects of increased household income under three anti-poverty economic support program packages found potential reductions of 11 to 20% in CPS investigations annually. Relatedly, a study of a home-based family preservation program found additional cash supports to help families with concrete emergency insufficiencies—such as utility payments, food, clothing for children, or transportation assistance—resulted in reduced likelihood of experiencing a subsequent child maltreatment report than families receiving no concrete supports.

Inversely, there is also a clear connection between reduced access to concrete and economic supports, such as social assistance in the form of programs like TANF, and increased involvement in the child welfare system.

ix For example, recent research has found a 23% increase in substantiated neglect reports, a 13% increase in foster care entries due to neglect, and a 13% increase in total foster care entries in states with more restrictive TANF policies, such as lifetime limits, bans for drug-related felonies, and limited transitional supports for newly employed parents.

The creation of the title IV-E prevention program was an unprecedented step in recognizing the importance of working with children and families to prevent the need for foster care placement and the trauma of unnecessary parent-child separation. The title IV-E prevention program is part of a much broader vision of strengthening families by preventing child maltreatment, unnecessary removal of children from their families, and homelessness among youth. It provides an opportunity for states to dramatically re-think how they serve children and families and creates an impetus to focus attention on prevention and strengthening families as primary goals, rather than foster care placement as the main intervention.

Foster care is an extremely costly intervention, both financially and in the potential erosion of emotional health and well-being, as well as diminished productivity. One study estimates the lifetime economic burden of child maltreatment, based on 2015 investigations by child protective services, was $2 trillion.

xi Additionally, a Chapin Hall resource provided the cost savings associated with prevention through economic and concrete supports to families.

xii The Congressional Research Service estimates spending on prevention in title IV-E was approximately $183 million in FY2024 compared to nearly $4.8 billion in foster care and $4.7 billion in adoption and guardianship.

xiii Increasing utilization of available prevention funding and decreasing reliance on foster care may both reduce the cost to government and improve the well-being of families for the long term.

Additionally, research has demonstrated the impact of economic supports on the ability of parents to reunify with their children after a removal and for children removed from the home to remain with families in kinship care. For example, studies have found that mothers who lose access to cash assistance experience longer times before reunification than mothers who maintained benefits.

xiv xv These studies underscore the relationship between increased monetary resources and the increased likelihood of reunification.

We provide below a number of examples of possible actions TANF and child welfare agencies can take or strengthen in a range of areas. We encourage grant recipients to reach out to OFA and CB for support implementing the below strategies within their local contexts and in accordance with federal laws and regulations.

Establishing a Joint Vision and Strategy

TANF and child welfare agencies can work together to establish a joint vision and strategy in the following ways:

- Collect detailed TANF data at the state and/or local level in order to enhance both longitudinal research capabilities as well as cross-program impacts between TANF and child welfare. Comprehensive and accurate data can improve the ability to track the trajectory of households that received TANF, including their receipt of other cash welfare benefits and reasons for case closures. This will allow for greater insights into the utilization and impact of TANF, including child-only cases, intergenerational patterns of TANF receipt, relationship between caseload dynamics, and employment patterns.

- Work with the state, territorial, or tribal administering agency to understand the shared goals and opportunities of TANF and child welfare to allow for informed decisions to be made when developing budgets and plans for TANF funding allocations.

- Inform and support executive staff, budget officers, TANF and child welfare program staff, community leaders, legislators, and other key constituents about the shared goals of TANF and child welfare, including the frequent connection between poverty and child well-being.

- Seek technical assistance from OFA and/or CB regional staff to support the state, tribe, and territory goals.

- Identify and act on state and tribal TANF policy options that can increase concrete supports to families.

Prevention

Policies that increase family access to TANF benefits are associated with reductions in foster care placement.

xvi Increased benefit levels are also a predictive factor to reduce foster care placements. The following strategies are examples of prevention opportunities:

Financing and Investment Opportunities

- Target eligibility for families at risk of child welfare involvement and streamline access for eligible families

xviii with such practices as eliminating steps in the application process by allowing enrollment in one program to satisfy some eligibility requirements for another program.

xix - Increase basic assistance cash benefit levels so that they are more responsive to the cost of living.

- Demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of using TANF for families at risk of child welfare involvement through cost analysis inclusive of both government funds and opportunity costs for families if a child is placed in an out-of-home environment.

- Leverage existing research and evidence to influence budgetary decisions to focus dollars on upstream prevention services by making the case for direct access to meaningful benefit levels and concrete supports.

xx - Pass through and disregard 100 percent of child support payments.

xxi

Policy

- Establish non-recurrent, short-term benefit programs in accordance with 45 CFR 260.31(b)

xxii that can be used to support families experiencing a specific crisis situation such as economic crisis to maintain parent employment and housing stability and safety for families. - Direct cash assistance to short-term rentals and other expenses related to finding and maintaining housing (e.g., security deposits, application fees, and utility costs).

- Provide subsidies for transportation, which enable families to maintain employment as well as access a range of services including health care, behavioral health care, and child care.

- Provide immediate concrete supports for families with young children, including clothing, child safety supplies, and other basic necessities.

- Repeal “family caps,” which deny additional assistance to families who have a child while receiving TANF benefits.

xxiii

Systems Alignment

- Fund community-based supports for child welfare prevention or parenting supports for parents and caregivers experiencing economic need.

- Use Home Visiting programs to identify opportunities to use cash to support material goods related to the care, health, and safety of the child and family.

- Develop public-facing content, training materials, and other materials for educating the public to further understand the differences between poverty and neglect. Examples include the Building Better Childhoods Toolkit.

- Leverage existing access points to ensure that the public is aware of and can access all resources available for economic support (such as calling “211” and being directly connected to appropriate departments responsible for benefits determinations).

Supporting Kinship Care

Financing and Investment Opportunities

- Increase benefit levels and access to TANF cash assistance for relatives seeking formal kinship care.

- Establish comparable benefit levels between TANF child-only cases and formal kinship care payments.

Policy

- Ensure child support orders are in the best interest of the child and referrals are appropriate by maximizing the flexibility to close a case referred from other means-tested assistance programs if the IV-D agency deems it inappropriate to establish and enforce.

- Revisit the definition of “relative” to allow fictive kin

xxiv to qualify as a relative for the purposes of accessing TANF child-only grants.

Systems Alignment

- Maximize access to child-only cases for relatives seeking formal kinship care and strengthen relationships between TANF agencies and State Kinship Navigator programs to support appropriate referrals.

Reunification

Given the association between financial resources and reunification, efforts to minimize the negative financial impact of a child’s out-of-home placement on parents have the potential to improve chances for reunification.

xxv

Financing and Investment

- Become familiar with the various state, territorial, and tribal programs that are driving promising outcomes for family preservation and stabilization by using TANF funds for concrete and economic supports to scaffold increased support of your goals.

Policy

- Implement flexibilities to promote successful reentry and reunification for families impacted by substance misuse, including removing or modifying lifetime bans for drug-related felony convictions through state legislation. Research indicates that families impacted by substance misuse in states that have suspended or modified lifetime bans have increased economic stability and reduced recidivism.

xxvi - Allow parents with children in foster care who are actively seeking to reunify to continue to receive TANF cash assistance to ensure children return safely to their own homes or the homes of relatives.

Systems Alignment

- Coordinate between child welfare agencies and TANF administering agencies so that the parent receives good cause for not participating in TANF work activities while the child is out of the home and the parent can participate in required reunification plan activities.

- Collaborate between child welfare agencies and TANF administering agencies to ensure TANF work requirements are not a barrier to successfully completing reunification plans so that TANF recipients can fulfill their participation requirements while also meeting reunification plan requirements such as parenting classes, substance use treatment, anger management classes, and counseling.

State Examples

- Chapin Hall released a brief highlighting promising state examples, TANF and Child Welfare Innovations.

Call to Action

When we invest in America’s families, we can prevent child maltreatment and build programs that create pathways for intergenerational well-being. Through collaboration across child welfare and economic supports programs like TANF, we have an opportunity to prevent and resolve the poverty-related challenges that lead families into child welfare system involvement unnecessarily, causing trauma and harm to families and limiting the potential for all parents and children to thrive.

OFA and CB will continue to work alongside you to coordinate policies and leverage funding to build innovative solutions that support families’ economic stability, prevent the associated risk of child maltreatment, and remove barriers to reunifying families as quickly and safely as possible.

In Partnership,

/s/ Rebecca Jones Gaston, Commissioner, ACYF

/s/ Ann Flagg, Director, OFA

_____________________

i Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2023). Separating poverty from neglect in child welfare. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/resources/separatingpoverty-neglect-child-welfare/

ii Rosinsky, K., Fischer, M., & Haas, M. (2023). Child Welfare Financing SFY 2020: A survey of federal, state, and local expenditures. Child Trends. doi: 10.56417/6695l9085q. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/childwelfare-financing-survey-sfy2020

iii Congressional Research Service. (2024, April). The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10036

iv Kim, H., and Drake, B. (2023). Has the relationship between community poverty and child maltreatment report rates become stronger or weaker over time? Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 143.

v Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., & Li, S. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, executive summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

vi Anderson, C., Grewal-Kök, Y., Cusick, G., Weiner, D., & Thomas, K. (2023). Family and child well-being system: Economic and concrete supports as a core component. [PowerPoint slides]. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

vii Puls HT, Hall M, Anderst JD, Gurley T, Perrin J, Chung PJ. State Spending on Public Benefit Programs and Child Maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2021 Nov;148(5):e2021050685. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050685. Epub 2021 Oct 18. PMID: 34663680.

viii Cusick, G., Gaul-Stout, J., Kakuyama-Villaber, R., Wilks, O., Grewal-Kök, Y., & Anderson, C. (2024). A systematic review of economic and concrete support to prevent child maltreatment. Societies, 14(9), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090173

ix Ginther, D. K., & Johnson-Motoyama, M. (2017). Do state TANF policies affect child abuse and neglect? University of Kansas. https://www.econ.iastate.edu/files/events/files/gintherjohnsonmotoyama_appam.pdf

x Ginther DK, Johnson-Motoyama M. Associations Between State TANF Policies, Child Protective Services Involvement, And Foster Care Placement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022 Dec;41(12):1744-1753. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00743. PMID: 36469816.

xi Peterson C, Florence C, Klevens J. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse Negl. 2018 Dec;86:178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.018. Epub 2018 Oct 8. PMID: 30308348; PMCID: PMC6289633.

xii Chapin Hall. (2024, June). A preventable cost: Economic burden of child maltreatment and child welfare involvement. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Cost-Savings-from-Investing-in-Children-and-Families_Chapin-Hall_6.3.2024-1.pdf

xiii Congressional Research Service. (2024, May 16). Child Welfare: Purposes, Federal Programs, and Funding. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44266

xiv Wells, K., & Guo, S. (2004). Reunification of foster children before and after welfare reform. Social Service Review, 78(1), 74–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/380766

xv Kortenkamp, K., Geen, R., & Stagner, M. (2004). The Role Of Welfare and Work in Predicting Foster Care Reunification Rates for Children of Welfare Recipients. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(6), 577–590.

xvi Ginther DK, Johnson-Motoyama M. Associations Between State TANF Policies, Child Protective Services Involvement, And Foster Care Placement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022 Dec;41(12):1744-1753. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00743. PMID: 36469816.

xvii Paxson, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2003). Welfare reforms, family resources, and child maltreatment. J. Pol. Anal. Manage., 22: 85-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.10097

xviii Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022). Chart Book: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) at 26. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/chart-book-tanf-at-20

xix Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (n.d.). Opportunities to streamline enrollment across public benefit programs. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/opportunities-to-streamline-enrollment-across-public-benefit-programs

xx Grewal-Kök, Y. (2024). Flexible funds for concrete supports to families as a child welfare prevention strategy (Meeting Family Needs series). Chapin Hall.

xxi Chen, Y., & Harper, K. (2023). Six strategies to design equitable child support systems. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/blog/six-strategies-to-design-equitable-child-support-systems

xxii As defined in 45 CFR 260.31(b)(1):

- Designed to deal with a specific crisis situation or episode of need;

- Not intended to meet recurrent or ongoing needs; and

- Will not extend beyond four months.

xxiii Shrivastava, A., & Thompson, G. A. (2022). Policy brief: Cash assistance should reach millions more families to lessen hardship. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/policy-brief-cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families

xxiv Fictive kin often include people who are not related by blood, marriage, or adoption, but who have an emotionally significant relationship with the child and those who are treated “like family.” (American Bar Association, Legally Recognized Fictive Kin Relationships: A Call for Action, March 1, 2022).

xxv Hook, J. L., Romich, J. L., Marcenko, M. O., Kang, J. Y., & Lee, J. S. (2015). Financial stability improves chances of family reunification. Center for Poverty Research Policy Brief: Volume 4, Number 4. https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/policy-brief/financial-stability-improves-chances-family-reunification

xxvi Haider, A., Goran, A., Brumfield, C., & Tatum, L. (2022). Re-Envisioning TANF: Toward an Anti-Racist Program That Meaningfully Serves Families. Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. https://georgetownpoverty.org/issues/re-envisioning-tanf.

PAST EVENTS

LOUSIANA

Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Information Center of Louisiana is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting.

Topic: 29th Annual Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Conference

Time: Apr 25, 2025 08:00 AM Central Time (US and Canada)

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/

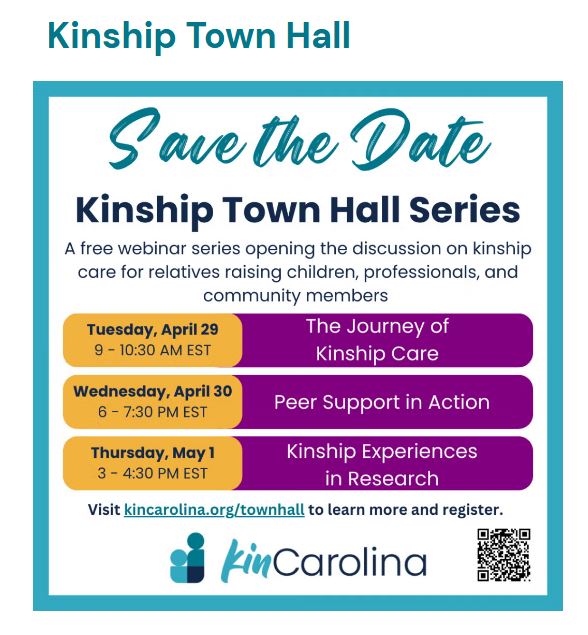

NORTH CAROLIONA

All Kinship Town Hall sessions are now eligible for FREE Continuing Education credits (CEs) for licensed social workers, psychologists, and counselors!